The First International Spaceflight

Today marks the 50th anniversary of the first joint international space flight and docking in space between the United States and the Soviet Union. Here is brief look at this historical event.

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of the first international joint spaceflight. After the completion of three Skylab missions in 1974, but before the first launch of the Space Shuttle in 1981, American manned spaceflight entered into a lull, interrupted only by the final remaining Apollo spacecraft forming a link with a Soyuz orbital ferry which was launched by our geopolitical rival, the then Soviet Union.

The Road to Cooperating in Space

This mission originated from a cooperative agreement that was reached during the Détente era in American foreign policy. On 24 May 1972, one month after the fifth lunar landing by Apollo 16, President Richard Nixon signed an accord with Premier Aleksei Kosegin in Moscow. The signing ceremony featured the two heads of state surrounded by an array of supporting dignitaries, including National Security Advisor (and later Secretary of State) Henry Kissinger, then Secretary of State (and later Chairman of the Challenger Shuttle Disaster Investigation) William Rogers, and General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev (the de facto Soviet leader via the Communist Party).

After a hiatus following the second Voskhod mission in March 1964 which included the first spacewalk, the Soviet Union resumed manned spaceflight with a new design. For improved utility over the Vostok derived capsules, Soyuz included an orbital module for operations and docking, a descent capsule, and an equipment module for sensors, communication, propulsion and power. Progress orbital supply vessels employed the same architecture. Following the successful unmanned test of Kosmos 140, the Soviets resumed manned missions with their debut flight of Soyuz 1 in April 1967. Tragically that maiden spacecraft suffered cascade failures, resulting in a fatal crash that caused the death of its single cosmonaut.

Following redesign and additional unmanned tests, manned flights with Soyuz 3 resumed in October 1968, a few days after America’s successful conclusion of the first Apollo manned flight. The Soviet design had been originally intended for three occupants, however, the sudden depressurization in 1971 of Soyuz 11, which led to the asphyxiation of all three crew in orbit, necessitated restriction to only two. Subsequent improvements enabled resumption to three cosmonauts aboard after 1980.

Further refinement of Soyuz enabled the Soviet and later Russian space programs to regularly launch crews into low earth orbit and to recover them on land. Operations included missions to several Salyut platforms, the Mir orbiting laboratory, and the International Space Station. Over the past half-century that initial design has been upgraded to several enhanced variants (T, TM, TMA, TMA-M and MS) with over one-hundred fifty manned flights. Soyuz will ultimately be withdrawn from service when Orel replaces this venerable workhorse sometime later this decade.

In October 1968, after nearly two years of design modification in the wake of an internal fire on the launch pad that killed all three astronauts inside the command module, NASA launched Apollo 7 with command and service modules with a three-man crew. Apollo was specifically designed for ferrying astronauts to the moon and back. The spacecraft was divided into modules to serve particular functions and was comprised of a pressurized command module that contained crew seats, instrument panels and an ablative heat shield for atmospheric reentry, together with a service module for propulsion and containing fuel cells for power supply. Moon landing missions further included a separate lunar module which was contained in the third stage of the massive Saturn V launcher. Unlike the Soviets with their Soyuz program, Americans discontinued the ambitious Apollo project after the conclusion of their sixth manned lunar landing.

NASA repurposed the remaining Saturn V booster, converting the third stage into the Skylab space station. From May 1973 to February 1974, three separate crews launched aboard Apollo orbiting spacecraft to intermittently dock and inhabit Skylab for the purpose of conducting repairs and experiments. This marked the end of Apollo’s lunar landings and space station visits. Later, Skylab reentered the atmosphere in mid-1979, eventually disintegrating over the Pacific Ocean. Yet, Apollo was due for an encore.

Two Rivals, One Joint Mission

NASA and the Soviet space program Kosmicheskaya programma (later succeeded by Roscosmos) was coordinated to execute the joint mission called the Apollo Soyuz Test Project (ASTP). The Soviets launched their 7 ½-ton Soyuz custom model 7K-TM with two cosmonauts from Kazakhstan, followed by the American 16-ton Apollo with three astronauts and a 2-ton pressurized docking module atop a Saturn IB booster from Florida. Apollo was tasked to retrieve the docking module from the second stage bay, and would undertake orbital maneuvers to rendezvous with Soyuz, which was equipped with a custom interface that was created specifically for this mission.

During approach, the two spacecraft would connect together via the docking module, after which the crews could congregate in orbit through hatches at the spacecrafts’ forward ports. By the mid-1960s, both space programs had successfully accomplished integrated spacecraft rendezvous and docking operations, which ultimately became routine.

For this project, the Soviets chose cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeri Kubasov, while NASA selected astronauts Thomas Stafford, Vance Brand and Deke Slayton. Both crews are shown together in the group photograph (seated left-to-right are Slayton, Brand and Kubasov, behind whom stand Stafford and Leonov between their flanking national flags).

Leonov, Stafford and Kubasov were space veterans: Leonov (d. 2019) had performed the first (and nearly fatal) spacewalk aboard Voskhod 2 in 1965, commemorated in the Russian docudrama Spacewalker (originally released as Vremya Pervykh). Kubasov (d. 2014) previously flew aboard Soyuz 6 in 1969 and subsequently flew again aboard Soyuz 36 in 1980.

Stafford (d. 2024) had first flown aboard Gemini 6A in 1965. He commanded Gemini 9A in 1966 and Apollo 10 in 1969. Brand later commanded STS-5 aboard Columbia in 1982, STS-41B aboard Challenger in 1984 and STS-35 aboard Columbia again in 1990. As one of the original Mercury astronauts, Slayton (d. 1993) had been grounded by a heart irregularity and served as astronaut manager. He returned to flight status in 1972 for his sole space mission as docking pilot, becoming the oldest person in space at that time. The colorful ASTP mission patch lists both crews respectively, in both Roman and Cyrillic alphabet characters.

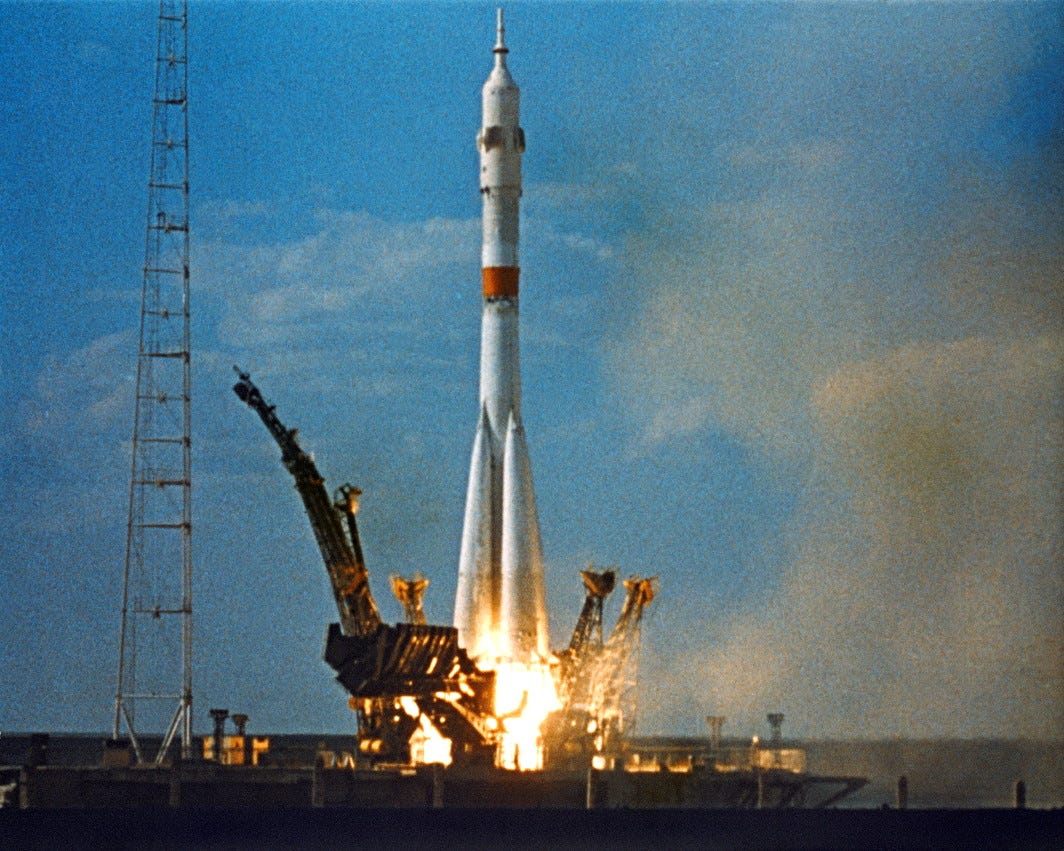

After months of mission preparation and learning their counterparts’ languages, the crews and their backups awaited their momentous occasion. Then, on 15 July 1975, a Soyuz-U booster launched Soyuz 19 into orbit from the Baikonur cosmodrome with Soviet mission control operated from Moscow.

A few hours later, a Saturn IB lifted the remaining Apollo spacecraft into orbit from Cape Canaveral. American mission control was directed from Johnson Space Center in Houston.

Upon orbital approach, Apollo was able to photograph Soyuz 19.

Meantime, Soyuz 19 photographed Apollo with its docking module.

After docking shortly past noon Zulu time on the 19th, the crew shook hands in the title photograph showing Stafford and Leonov. The five men conducted science experiments, exchanged mementos, and crews from the two spacecraft practiced release and re-docking maneuvers. Both superpowers deemed the mission as successful, from both a technical and a public relations perspective. Kubasov and Stafford are pictured below.

After almost four days together, the two spacecraft separated. Soyuz 19 reentered the atmosphere landing in the Kazakh steppe on 21 July. Apollo continued its experiments and splashed down on 24 July, retrieved in the Pacific Ocean by the amphibious assault vessel USS New Orleans (LPH-11). During descent, toxic fumes from hypergolic propellant leaks contaminated the cabin, requiring hospitalization for the three recovered astronauts.

Aftermath and Continued Cooperation

Unfortunately, neither country sought to repeat this encounter. Development of the technologically challenging reusable Space Shuttle preoccupied American efforts, while foreign engagement lay dormant in the wake of the U.S.’s withdrawal from South Vietnam. The Soviets aggressively pursued international hegemony during the somnambulant Carter administration, while at the same time suffering economic stagnation through diplomatic intimidation and military overtures.

While Americans remained earthbound, the Soviets continued international space flights unilaterally beginning in March 1978 with Soyuz 28, which included a Czech cosmonaut aboard the Salyut 6 space station. Further missions followed, initially from Warsaw Pact nations (Poland, East Germany and Hungary), expanding to other communist bloc countries in the early 1980s (Vietnam, Cuba, Mongolia and Romania), and then more broadly (France, India, Syria, Afghanistan, Japan, United Kingdom and Austria) before Soviet dissolution occurred at the end of 1991. Manned spaceflight was later continued by the Russian federation using the original Soviet infrastructure.

As Soviet leadership aged while America resurged under President Reagan in the early 1980s, NASA resumed manned operations with the Space Shuttle program, which ultimately included a fleet of five spaceplane orbiters: Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Atlantis, and Endeavour. The United States eventually adopted international cooperation in 1984 with the inclusion of a Canadian astronaut aboard Challenger, followed by a Saudi and a Mexican astronaut in 1985 respectively aboard Discovery and Atlantis. After the loss of Challenger, NASA suspended international Shuttle flights until 1992. The first Russian cosmonaut joined STS-60 aboard Discovery in 1994.

Eventually, shared cooperation resumed between Russia and the United States. American missions to the Mir station commenced in 1995 with Shuttle rendezvous approaches, followed by the first American astronaut being lifted to space aboard Soyuz TM-21 in March. Almost twenty years after ASTP, STS-71 with Atlantis docked with Mir in June that same year. Over the next three years, seven astronauts visited Mir via Soyuz, and a total of nine Shuttle missions docked with the station, with most of those missions being accomplished by Atlantis, as shown below.

An international consortium produced various components for the joint assembly to form the International Space Station (ISS), which was originally proposed in 1984. Years of tradeoffs yielded the first Russian and American components being launched in late 1998, with continuous occupation since November 2000. NASA dedicated thirty-six Shuttle flights (more than a quarter of their total) to the ISS construction and supply, as well as to the task of bringing astronauts aboard the station. STS-134 with Endeavour conducted the last mission to the ISS, which are shown below docked together.

After the Space Shuttle’s 2011 retirement (in the wake of the 2003 loss of Columbia) and before the 2020 maiden launch of an occupied Dragon capsule by SpaceX on a Falcon 9 launcher, American astronauts relied on the Soyuz platform to ferry them to the ISS. Despite Russia’s invasion of Ukraine souring these continuing efforts, the current Expedition 73 aboard ISS comprises a complement of three Russians, three Americans and one Japanese, ferried into orbit by Soyuz MS-27 and Dragon Crew 10.

Around the end of this decade, the ISS will eventually be de-orbited, and further cooperation will necessitate new negotiations for replacement orbiting platforms, which may be funded either publicly or privately. Looking back, the Apollo Soyuz Test Project demonstrates that technological cooperation is possible even among rivals with who have opposing geopolitical ambitions, particularly in an arena that is hostile to all human life.

Photo Credit- Photo Credits- Encyclopedia Britanica, Wikimedia, ninfinger.org, pinimg.com, shymkent.info, hdnux.com, live.staticflickr.com, nasamedia.lunaimaging.com, collectspace.com, s3.amazonaws.com, wallpapersafari.com, rare-gallery.com,

An excellent article on the history of these two countries space program. I still have have plenty of memorabilia from this time, including the original 'coin' minted for this joint flight as well as postage stamps from both countries celebrating this event. (Plus plenty of flight patches for these programs from the 70's and 80's.)

The early enthusiasm from the space programs has long passed, something I think most of today's youth cannot relate to. Likely one large reason why pride in this country has fallen.

Thanks for sharing.