Modern Lessons from the Great Mouse Utopia Experiment

John Calhoun's famous Mouse Utopia provided a template for what happens when a society collapses, not from adversity, but from too much comfort and security. Is this where our culture is today?

In the late eighteenth century, the Reverend Thomas Malthus published An Essay on the Principles of Population, which warned of population increase overtaking food production, thereby necessitating a reduction in world birth rates. Since then the specter of “overpopulation” became a popular apocalyptic topic among the intelligentsia. Such dystopian concerns gradually ameliorated as human ingenuity improved living standards across the globe. However, in the meantime, another related trend appeared – urban atomization – in which the quality of social interactions diminished as people crowded together anonymously in large cities.

At the National Institutes of Health, John Calhoun (a research ethologist, not the seventh vice president) conducted numerous experiments on rodents – specifically Norway rats and house mice – in colonies within enclosed structures that he provided with adequate water, food, room and nesting materials, while seeking to avoid disease. The social pathologies exhibited by the experiment pointed to eventual population collapse. Calhoun extrapolated these behaviors to human interactions that could inhibit flourishing, positing that while individual mortality would be typically attributed to external physical conditions, such as starvation or predation, “vice” or adverse social interaction among fellow species members could adversely affect population continuance. These degenerative patterns were labeled as a “behavioral sink” by Calhoun.

Calhoun published his findings, which included two oft-cited articles: “Population Density and Social Pathology” in Scientific American (Feb. 1962) involving rats, and “Death Squared” in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine (Jan. 1973) using mice. Other similar experiments conducted over his career reportedly presented similar results. The alarming results have attracted public attention with attendant cultural influence.

The First Rat Colony Experiment

The rat colony in the 1962 report was partitioned into four pens within a room measuring 10 feet by 14 feet, and was observable from a ceiling window. The pens were separated by electrified fences, and three of these were interconnected by ramps. Calhoun conducted six experiments for study across sixteen months each, beginning with a population of 32 rats for the first three, and 56 rats for the remaining three, evenly divided by sex, using rats that were just past the weaning stage. In each case the rats were provided adequate food, water and nesting materials, as well as the elimination of both predators and disease, but crucially no ability to escape from the enclosure. Their numbers increased until reaching 80 adults by the twelfth month, after which infants that survived until weaning were removed to hold the populations steady.

As observed in the study, dominant males territorially guarded the ramps to protect their harems. The females initially became pregnant and consciously raised their pups. Submissive males crowded together for feeding and drinking (as fostered by delays induced by the hopper design); they avoided sexual interaction with the females while attempting to mount the dominant males, who tolerated such advances. Due to dominant males restricting ramp access, the middle pens witnessed the highest population density and sex imbalances from group segregation.

In the middle pens, males divided into hierarchies. A dozen or so aggressively fought for dominance, while pansexual advancers showed somewhat less activity. Somnambulant males kept to themselves while maintaining their sleek fur, while probers hyperactively engaged other males and pursued estrous females even within their burrows, in contrast to typical heterosexual male rat behavior of “courtship” waiting. Crowding distracted the dominant males, while disrupting the intense (primarily female) activity of nest building from the ample paper strips supplied. Pups that previously would be carefully carried from one burrow to another were subsequently abandoned by their mothers. In addition, Probers would cannibalize the dead pups in untended burrows.

By the sixteenth month, mortality among the females and young had increased to the extent that social trauma and reproductive failure would lead the colony to die out. Mortality affected females more from pregnancy and parturition. Gradually, crowding led to females having fewer births and decreased pup survivability – only four percent in the first experiment and twenty percent in the second. At the end of the first experiment, all but the eight of the healthiest rats were culled, but no offspring survived to maturity, despite the end of crowding.

The “Universe 25” Mice Experiment

Calhoun’s subsequent report employed albino laboratory-bred house mice within an escape-proof temperature-moderated square enclosure, each side extending 101 inches with walls 54 inches high. Apartments for nesting, food hoppers, water bottles and nesting material provided accommodation for at least 3840 mice distributed among the sixteen angularly distributed cells. Even at the peak population of 2200 mice, about twenty percent of nest sites remained unoccupied. This mouse utopia has been called “Universe 25” in the literature and on the Internet.

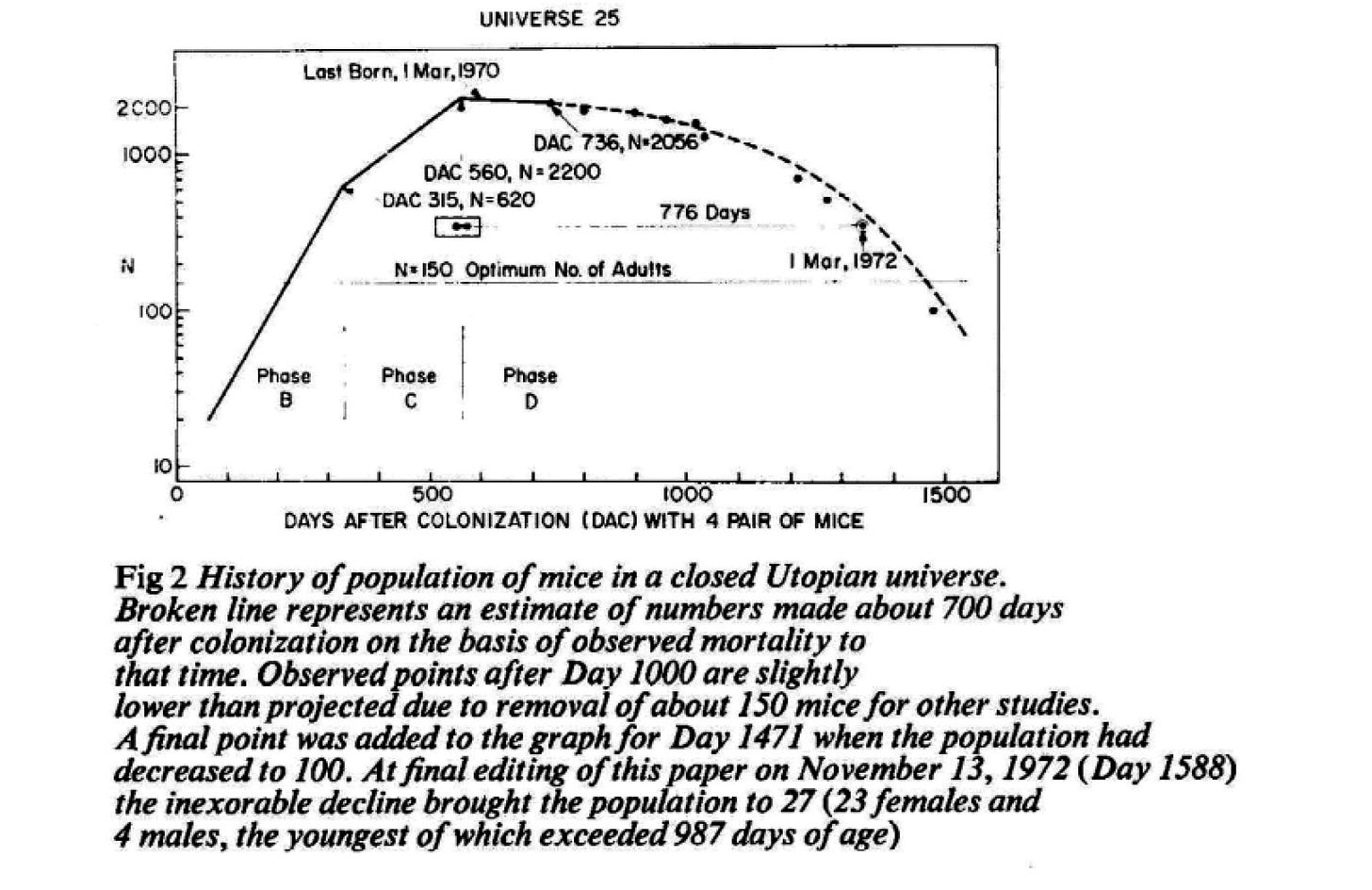

Four pairs of 48-day old mice were introduced in July 1968. The first 104 days (Phase A) exhibited social turmoil as the mice adjusted to their environment. Then, the population doubled five times until reaching 620 mice (Phase B) at 315 days after colonization (DAC). A slower growth period (Phase C) continued until peak population of 2200 mice at 560 days. Calhoun noted that a mouse at age 800 days would be equivalent to a human at 80 years. Demographic expansion during the growth phases (B and C) provided a measure of status rank, with active dominant males siring larger broods than those of lesser order.

The population leveled off (Phase D) and then precipitously decreased with no reproductive females remaining. Autopsies of females after population inflection revealed only eighteen percent had conceived and only two percent had been pregnant. The last surviving birth occurred by day 600, and the last conception occurred about day 920. By day 700, the colony’s population trajectory had reached terminal status, with estimates of the last surviving male perishing about day 1780. These results are illustrated in the population semi-logarithmic graph below. Note that the metric “DAC” refers to days after colonization.

Non-reproducing females had male counterparts that would devote efforts to grooming but no mutual interaction. The younger generation of mice failed to develop the capacity of bearing and raising offspring. This inability persisted even after transferring them to low density environments with opposite-sex counterparts that had matured in uncrowded conditions.

The study found that when social positions within a community reach saturation, the misfits depart for harsher and thus less competitive environments, i.e., scarcer resources with greater predation. However, the closed environment precluded such emigration, trapping non-dominant male mice in an unaccommodating social network. Disruption in nurturing activities by antagonistic hostile members, such as was evident previously with rats, inhibited female mice from birthing and raising pups. Much as in the 2005 movie Serenity, the debilitating effect of artificially tranquilizing Miranda’s population led to mass suicide. Calhoun called this despondency the “first” death, with physical morality being the “second.”

Mouse utopia and related rodent population experiments suggest that removal of Malthusian resource impediments lead to inescapable dystopian nightmares. But this merely shifts the question of cause and leads to the question: what precisely is the culprit? overpopulation? densified crowding? inadequate social integration? absence of non-human predators? insufficient pathogens? inability for misfits to leave? Does the Dunbar number impose practical limits on human social complexity? Can humans by cognitive intellect or religious assurance overcome the despondency that rodents lacking a cerebral cortex cannot? What should we do? That is the sixty-four dollar question.

Modern Lessons from Our Culture’s Behavioral Sink

Peter Turchin proposes that declining human societies produce too many claimants of elevated status. A properly meritocratic society would shunt such mediocre grifters who seek fame and fortune primarily by crony entitlement (from pedigree, such as family connections in the past, or academic credentials from prestigious colleges today) rather than innate talent and personal industriousness. Anxiety over uncertainty from absence of such qualities in a changing landscape that might actually call them into account for useful traits other than “diversity” has become evident in political psychosis. Meritocracy interferes with the Left’s campaign to elevate their “diversity” driven mediocrity to dominance and consequently supplant capable persons with intersectionally marginalized incompetent replacements. Although tradeoffs can be analyzed to foster domestic tranquility, society should resist the pseudo-intellectual power grab from the woke, who will maintain their desire for political and cultural dominance.

Before the election, journalist Mark Halperin predicted a leftist mental health crisis during his interview with Tucker Carlson. Sure enough, after Trump’s inauguration, pundits wrung their hands over their unexpected change in fortunes, expressing their grief in Salon, Scientific American and Rolling Stone, among other venues. Meantime, other Kamala Harris acolytes doubled down as childless cat ladies, eager to lampoon the non-degreed incels they refuse to date (while at the same time oblivious to the mutual disdain that eligible men might have towards misandrous Trigglypuff doppelgangers), assuming their myopic management hasn’t eviscerated excitant economic opportunities.

While societies can withstand grifters at various institutional ranks, eventually these become so damaging from cumulative incompetence that backlash becomes inevitable, as witnessed in the latest presidential election between an enormous and effective political machine and an inchoate but frustrated collection of ostracized citizens weary of being disregarded by their putative betters. Although the current struggle between elites (wealthy entrepreneurs versus institutional establishment denizens) relegates the mass audience to mere spectators, most of Trump’s supporters favor the group that they believe hates them less – and that certainly does not include the mid-wit managerial class who have for many years remained in charge of regulating their lives and livelihoods.

Meanwhile, with total fertility below the replacement rate across almost all developed nations, our societies face the conundrum of attempting to avoid eventual demographic collapse. Aside from encouraging de-urbanization and improving employment prospects for the citizenry, what can be done at large to avoid demographic collapse? Current efforts by governments around the world tragically show little promise.

Perhaps humans will be unable to recover from all of this, absent some external and recognizable threat to unite against. Perhaps the feminists are correct, that “the future is female” and the “patriarchy” will vanish with the disappearance of men, leaving an apocalyptic landscape, although feminists will likely continue to fantasize about achieving their own girl boss freedom. Perhaps the opposite is more likely, with women being replaced by artificial wombs or by cloning. Perhaps philosophical and religious revivals will re-enchant the public with the desire to invest less in singular self-fulfillment and instead towards diligent care and the education of children. Calhoun’s controlled environments presented glimpses into non-Malthusian conditions run amuck. Our society may not be sufficiently wise or discerning as to decide how to heed the warnings, but it pays to be aware of them, nonetheless.

Photo Credit- Scientific American

Science is nature. Another example that proves the left's anti-nature agendas are anything but following the science. As I dig deeper into the writing world, I am seeing more and more leftists with mental health issues. They flock to their writing, trying to create their own reality with stories about how dark the world is and how they are suffering from society without realizing that they are their own worst enemies. Their writing is usually not uplifting, fun, or supportive of traditional families. They push to make the rest of the world fake like their own, thinking it will make them happier - but it only destroys society and dragging it deeper into depression.

This intriguing article juxtaposes cultural shifts in urban life, mimicking findings from mouse experiments observed as far back as the 1800s.