Lunar Flyby

For the first time in 50 years NASA will (possibly this week) leave Earth's low-orbit and attempt a 10-day manned flyby mission to the moon.

NASA is preparing for the first manned lunar approach in more than five decades. Artemis II expects to be the first lunar flyby since the aborted ten-day mission of Apollo 13 in 1970. After recently mating the spacecraft and launcher, Artemis II has now been transported to Pad 39B.

If preflight propellant loading operations proceed successfully, launch will be scheduled within windows between the sixth through the eleventh of February, the sixth through the eleventh of March or the first through the sixth of April. These intervals will enable the crew to view the far side of the moon while it is illuminated by the sun, unlike the Apollo missions whose landings demanded visibility on the near side.

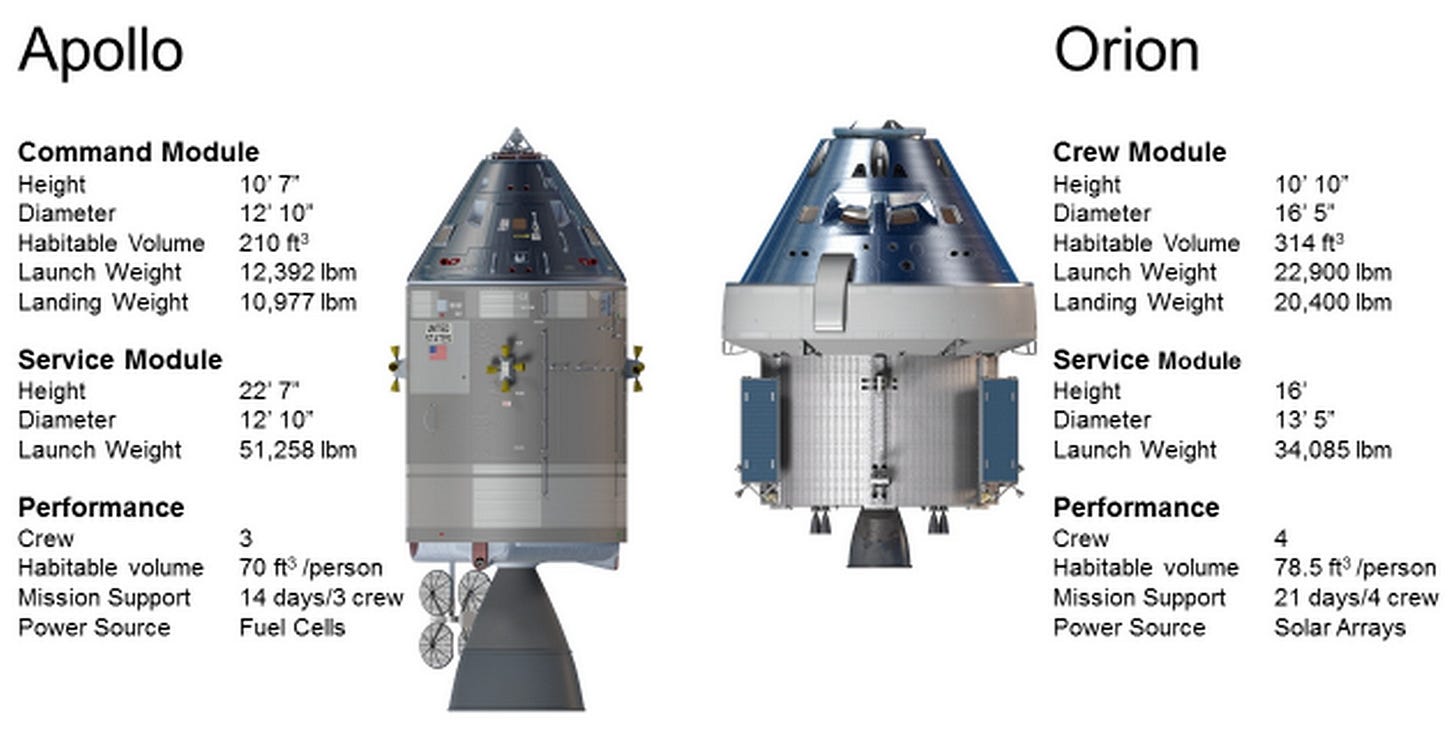

The 26.5 metric tonne Orion spacecraft includes separate crew (encapsulated in a launch abort system) and service modules, the former which provides support four astronauts, while the latter provides electrical power and propulsion. Lockheed is building the crew module, while the Airbus is supplying the service module, which includes solar panels that are designed to unfold. The Orion and Apollo spacecraft have comparable sizes as illustrated below.

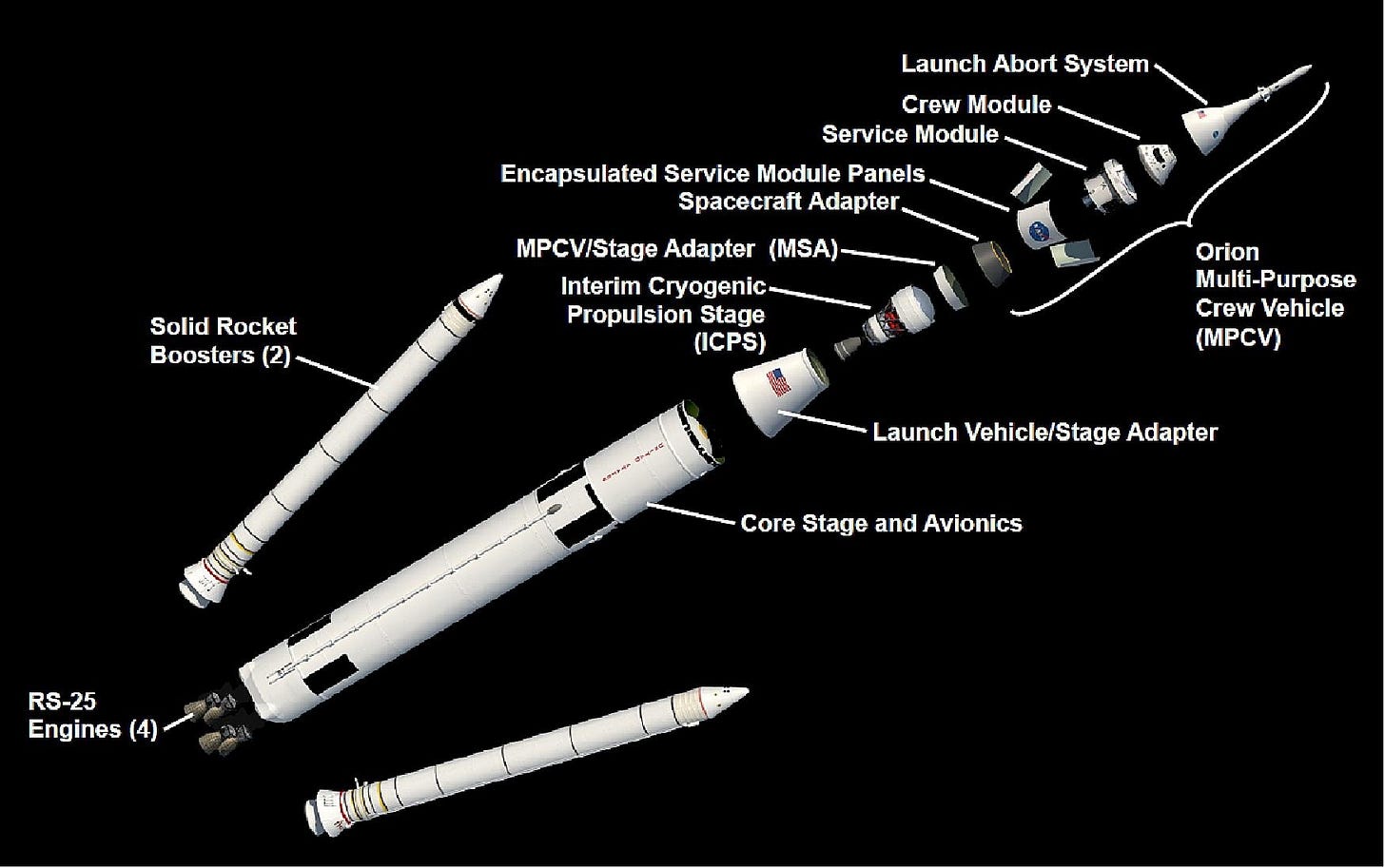

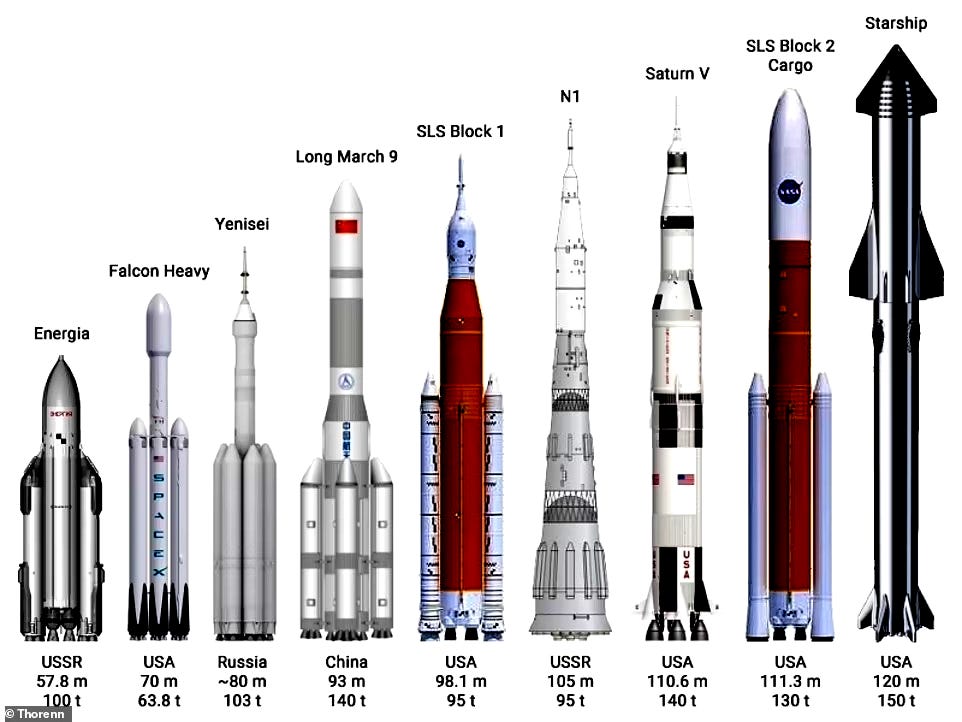

Lofting such a heavy payload into trans-lunar injection necessitates a massive booster – in particular the Space Launch System (SLS), which has a total thrust greater than the Saturn V, although less than SpaceX’s Starship. In contrast to Elon Musk’s rapid prototyping and testing approach of new hardware designs focused on reusability, NASA has chosen to follow a more incremental approach limited by one-time use for all components, which were derived from the retired Space Shuttle program. These include refurbished Shuttle’s RS-25 main engines from Rocketdyne and solid rocket motors made by Alliant. An exploded view is shown below.

Consequently, the liquid propellant contribution to rocket propulsion for the SLS mirrors its predecessor, the Space Shuttle, and the upper two stages mirror Saturn V. These designs employed cryogenic liquid oxygen (LOx) as oxidizer and liquid hydrogen as fuel. By contrast, Starship, although also using liquid oxygen, burns methane, which is denser than hydrogen and cleaner than traditional kerosene.

SLS can be compared to earlier and contemporary heavy lift boosters. Thorenn features (left-to-right) Soviet Energia, Falcon Heavy, Russia’s Yenesei, China’s Long March 10 (incorrectly labeled in the image), SLS Block 1, Soviet N1, Saturn V, SLS Block 2 and Starship. Their heights are identified in meters, and their payload mass to low earth orbit in metric tonnes.

SLS also includes a cryogenic upper stage with a LOx-hydrogen Rocketdyne RL 10B-2 engine (based on the venerable design by Pratt & Whitney) to propel Orion from low earth orbit into trans-lunar injection towards the moon. The first two Artemis missions operated with the Block I version of SLS, while upcoming planned missions intend to provide upgrades to the upper stage in the Block 1B and advances in the solid rocket motors and RS-25 Shuttle engines for the Block 2 variants (for increased payload capacity).

The crew selected for the crew module “Integrity” includes veteran American commander Reid Wiseman, pilot Victor Glover, and mission specialist Christina Koch, all of whom have previously flown to the International Space Station. The Artemis program recognizes international cooperation by including Canadian rookie Jeremy Hansen as an additional mission specialist. Wiseman served in the US Navy as Captain and launched on Soyuz TMA13M in 2014 before serving as Chief of the Astronaut Office. Glover served in the US Navy as Captain and launched on Dragon Crew 1 in 2020. Koch trained as an electrical engineer and launched in 2019 on Soyuz MS12 and returned the following year on Soyuz MS13. Hansen served in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

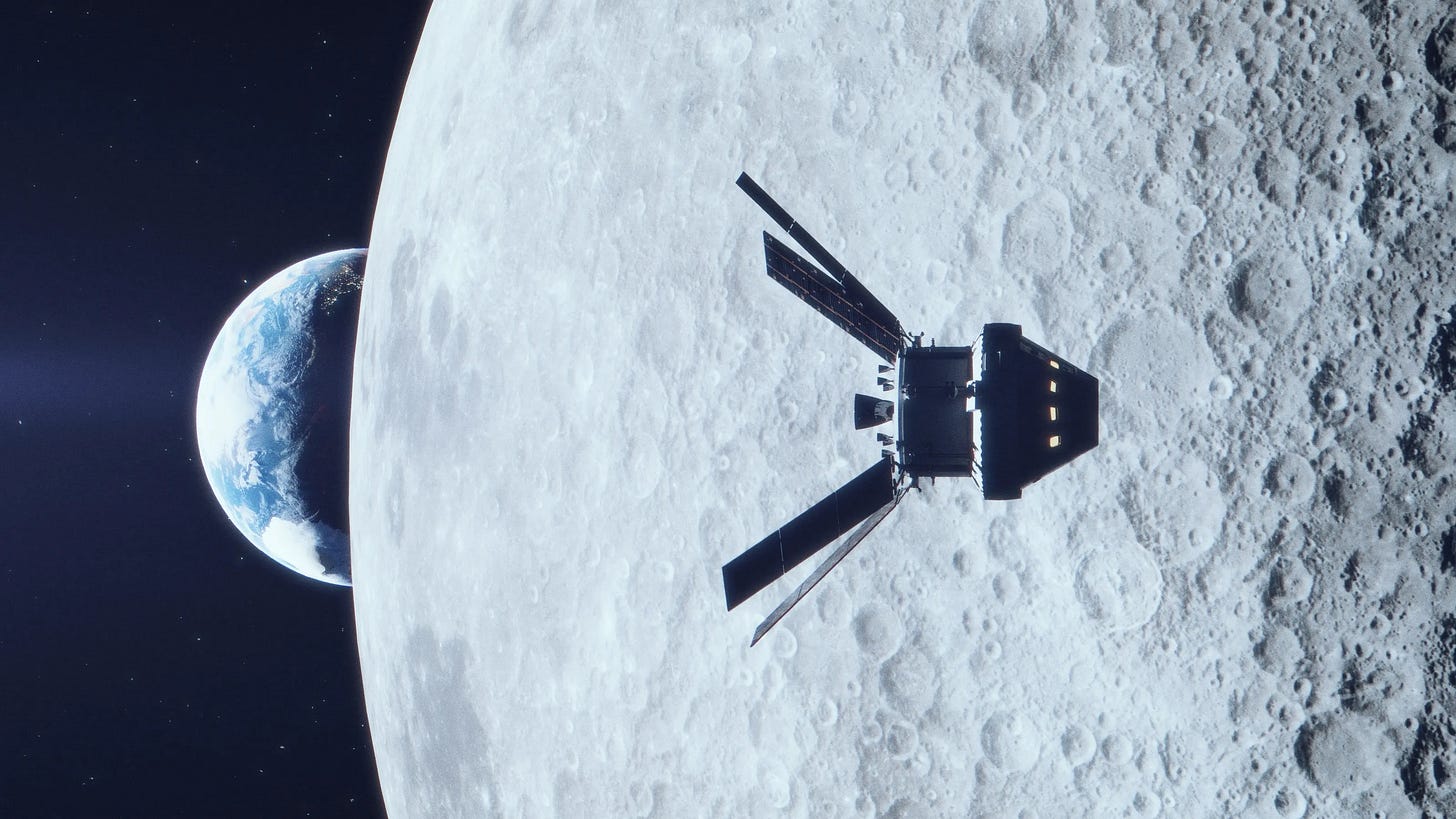

The first unmanned Artemis mission in late 2022 engaged in orbital maneuvers of Orion around the moon with its powerful launch (featured below). This second mission denotes the first time the Orion spacecraft will include humans aboard in flight, although serious concerns have been raised in that Orion’s life support systems have not been previously tested in orbit. Following launch, Artemis II will engage in checkout tests of onboard systems to ensure proper operation prior to the intended rocket engine by the upper stage burn to reach the moon. After separation, Integrity will rendezvous with the spent upper stage to test maneuver response. The free return trajectory using the moon’s gravity obviates the need for course changes.

The ablative heat shield constitutes another safety concern, in this case regarding atmospheric re-entry. It is composed of epoxy phenol formaldehyde resin within a fiberglass honeycomb. As the crew module reaches the thin upper atmosphere, friction induces deceleration, and thereby heats the exposed module’s surface. The heat shield dissipates the resulting thermal energy by phase change absorption and removal by charring and ablation.

Returning from the moon presents about forty percent higher speed than re-entry from the International Space Station. Kinetic energy is proportional to velocity squared, thereby doubling the thermal energy to be dissipated from low earth orbit. Moreover, the Orion crew module has twice the mass of the Apollo command module. Examination of the heat shield after the Artemis I revealed ruptures in the matrix from uneven charring (highlighted by the red rings shown below).

These results have led to suggestions to launch Artemis II unmanned. In a lengthy article, Casey Handmer presents a scathing critique of the Orion spacecraft and of the SLS booster, not only highlighting safety concerns, but also its high cost. Robert Zimmerman also echoes these warnings amidst the publicity for this historic (and hopefully non-tragic) event. Moreover, the Artemis program plans a multi-module docking station called “Gateway” for Orion, but has not developed a lunar lander, expecting such provision by either SpaceX or Blue Origin.

Whether Orion and the SLS have become superfluous for an American manned lunar return presents an open question. NASA appears committed to completing this trans-lunar flight, although the second Trump administration may decide to shift priority towards less bureaucratic approaches to hardware development, and reconfigure lunar landings with dedicated hardware using independently produced designs from the aerospace industry.

Photo Credits- NASA.

I’m only somewhat excited about this mission. Apparently it was just delayed another month. I have so little respect for NASA. I trust SpaceX to build a Tesla factory on the moon before NASA feels safe enough to maybe possibly orbit it. Looks like this was a crony operation with government favorites getting contracts.

Stellar technical overview. The heat shield issue from Artemis I is genuinely concerning given that lunar return velocities double the kinetic energy compared to LEO re-entry. I worked on thermal protection systems in aerospace and uneven charring like that usualy signals design assumptions that didn't hold under real conditions. The comparison between NASA's incremental approch and SpaceX's rapid iteration really highlghts two different engineering philosophies, both with tradeoffs around safety versus adaptability.