Iron Age II Cancel Culture

We tend to think of "cancel culture" as being a facet of our modern social media age. However, the desire to "cancel" the names and achievements of ones enemies is as old as civilization.

Erasure of disfavored personalities from social media is nothing new. In late Bronze Age Egypt during the fifteenth century BC, Hatshapsut – royal widow of Thutmose II – ruled as the sixth pharaoh of the eighteenth Dynasty. Later, both her step-son Thutmose III and grandson Amenhotep II had her images chiseled off from cartouches and monuments, while at the same time reassigning credit for temples and other buildings that were constructed during her reign.

Similar defacing reoccurred the following century when Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) replaced the god Amun with Aten – followed by policy reversal after his succession. In other example, the Athenians often destroyed inscriptions of former heroes they later condemned. Rome employed the Latin phrase “damnation memorae” (condemnation of memory) to label this practice. In AD 31, the Senate executed Consul and Praetorian prefect Lucius Sejanus (and his family), which included obliteration from public records, for poisoning Drusus, son of emperor Tiberius. Second century emperor Publius Geta suffered this same fate after his murder in AD 211.

Compared to the ancient Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilizations, the tribal states of the Levant that lay between them provide a paucity of surviving ancient texts. While climatic conditions rapidly decompose organic media, such as papyrus and parchment, the Egyptians commemorated their records on temple walls and obelisks at cities along the Nile with hieroglyphic memorabilia. And Mesopotamian civilizations such as Sumerians developed cuneiform – arranged sets of geometric wedges impressed onto clay tablets for baking into indelible records.

This latter technique proved so popular that fourteenth century BC Egypt corresponded with cities along the eastern Mediterranean via cuneiform in diplomatic dispatches. Archaeologists found a cache of these in Amarna from the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten. Assyrians were so prolific in record keeping that translations of their writings are compiled in tomes, such those as described in Ancient Records of the Assyrians and Babylonians by Daniel D. Luckenbill (in first and second parts). The third volume of Royal Inscriptions by Kirk Grayson presents transliterations from the first millennium.

By contrast, the entire ancient Levant has handfuls of monumental or other transactional inscriptions on stela or ostraca (pottery shards). Most of these date from the monarchial period, particularly Iron Age II – that archaeological period denoted by its red-slip ware – roughly from the tenth to eighth centuries BC and corresponding to 2 Samuel through 2 Kings and the first thirty-nine chapters of Isaiah. (The widespread collapse of Bronze Age civilizations in Ancient Near East enabled Israelite tribes to settle inland from the Mediterranean coast.) Their entire corpus is transcribed into modern Hebrew characters in a slim volume Kanaanäische und aramäische Inscriften (known as KAI) written by Herbert Donner and Wolfgang Röllig which consists of a mere 79 pages in the fifth edition (2002, Harrassowitz Verlag).

The paucity of extant written materials does not imply absence of literary capacity, as evidenced by repeated transcription of the Tanakh, as well as its source documents, by Judeans over the millennia. Levantine scribes drew visual representations of objects, which were analogous to hieroglyphs. Each image symbolized a phonetic utterance based on the object’s name. These symbols could then be used to visually register corresponding sounds in order to assemble an alphabet.

What did such text fragments look like? Those from ancient Israel reveal terse receipts or pleas. One of the earliest shards in Judges 6:32 names Jerubba‘al – an alternate name for Gideon – dates from the twelfth century BC. The Jerusalem Journal of Archaeology reported this discovery four years ago. In 1910, excavators found a cache of ostraca in Israel’s capital Samaria during Omri’s dynasty published in KAI under entries 183-188. Historical analysis suggests they date from the latter reign of Jehoahaz (2 Kings13:1) and the co-regency of his son Jehoash (2 Kings 13:10). These ostraca reveal commodity tax receipts or conscription muster in the late ninth century BC. Examples of numbers 14 and 18 indicate wine and oil, respectively. Another ostracon found in 1960 at Yavne-Yam presents a petition from a field laborer via a trained scribe to a local governor – published as KAI 200. The laborer requests return of his cloak that had been confiscated by an overseer. Such an act contravened Exodus 22:26-27 and Deuteronomy 24:12-13.

Outside of ancient Israel and Judah, various potentates erected monuments denoting military prowess. For example, Moab revolted after Ahab’s death (2 Kings 1:1; 3:5), and Mesha boasted his autonomy on a stele found in 1868. Before its recovery, local tribesmen deliberately broke apart the monument. Its inscription, dating to about 840 BC, clearly identifies Israel’s king Omri as their oppressor. Omri’s reign (1 Kings 16:23) provided stability and prosperity to Israel after years of civil war. To the north in Anatolia (modern Turkey), Kilamuwa celebrated his geopolitical accomplishments in Phoenician, dated to about 825 BC. KAI publishes texts of the Mesha and Kilamuwa stela as respective entries 181 and 24. Their scripts and images are shown below:

Over the generations that scribes composed and redacted the Hebrew scriptures from prior oral or written sources, textual anachronisms have cast aspersion of the cultic narrative. Such examples might seem minor in matters of faith, such as Abraham owning dromedaries (Genesis 24:10) prior to the domestication of camels several centuries later. Many scholars contest scriptural accounts of tribal settlement chronologies and related military campaigns. However, some critics go even further to dispute the historical existence of Israelite and Judean monarchies as administrative polities, condemning biblical literature as post-exilic religious fables.

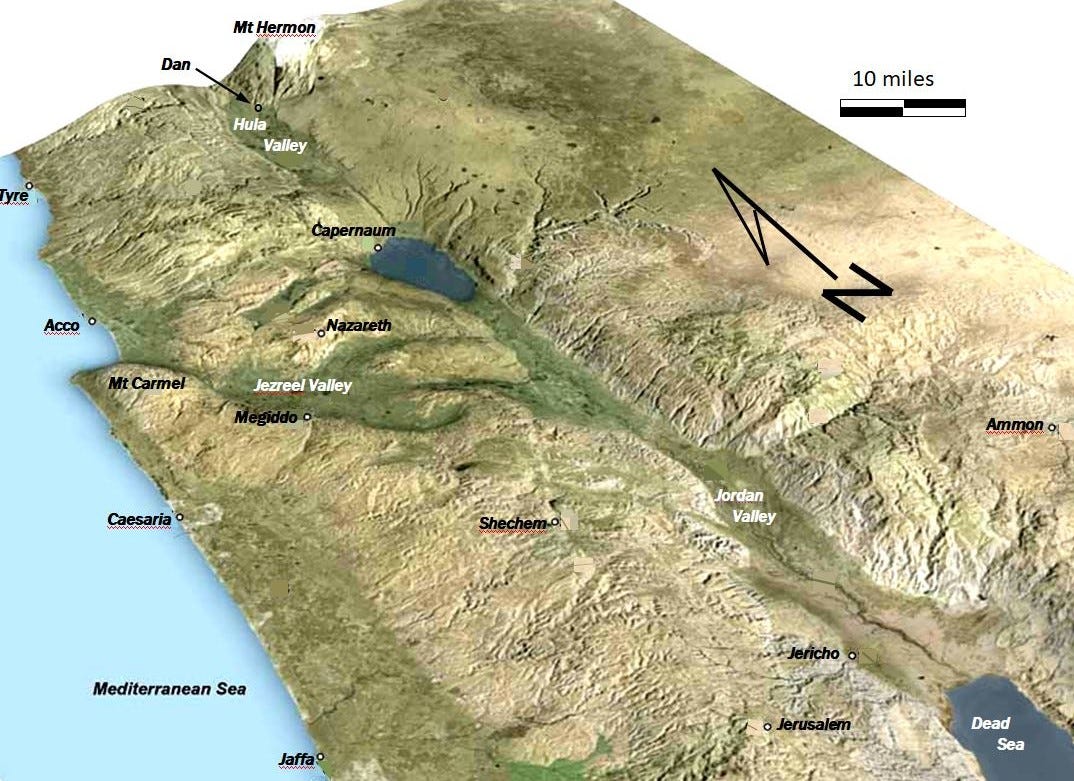

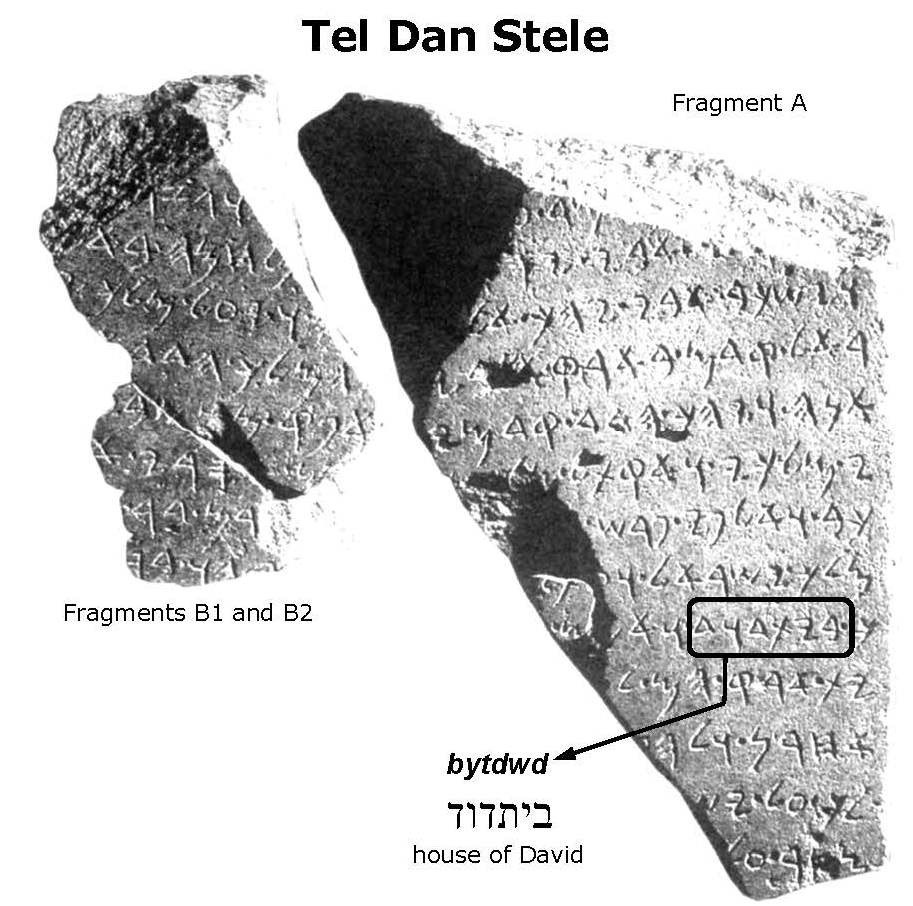

One such dispute focuses on evidence for a Davidic dynasty in Judah. In July 1993, archeologists found a stele fragment (later labeled “A”) at Tel Dan – near the northeast border of modern-day Israel. The relief map below shows Dan as due east of Tyre, the Phoenician city along the Mediterranean, and north of Capernaum in Galilee. The Ammonite and Moabite nations lie east of the Jordan valley, while Israel, Judah and Philistia occupied the western side. Well before the erection of the Tel Dan stele, Abraham gathered a posse to rescue his nephew Lot at Dan (Genesis 14:14), although the site had been Laish before its conquest (Judges 18:27-29). The following year, two smaller fragments (labeled “B1” and “B2”) were discovered originating from the same stele. Subsequent excavation has not revealed any additional portion(s).

Published as KAI 310, the fragments together cover an inscribed area of 1.2 square feet. For comparison, the more famous Rosetta Stone covers 6.8 square feet. Composed in Aramaic and written in North Semitic script, the stele’s incomplete text commemorates a battle in which Israel’s king became a casualty during Iron Age II.

The minimal weathering of the text’s lettering indicates that someone intentionally broke the commemorative basalt monument only a few decades after its completion and display. The larger fragment became a celebrated discovery, as this was the first unambiguous confirmation of David’s historicity in a contemporaneous secular document. The image shown highlights the word “byt-dwd” in reference to the House (i.e., linage) of David.

Too much of the text has been lost to identify the events described beyond the assertions that the Israelite king was defeated and killed, with participation by the Judean king. The consensus holds that this contest corresponds to the assassinations of Israelite king Joram and Judean king Ahaziah in 841 BC – reported in 2 Kings 9:24-29 and 2 Chronicles 22:7-9 – instigated at Jezreel by chariot commander Jehu. The stele credits this result to the leader of Aram-Damascus – presumably Hazael. Hebrew scribes noted (in 2 Kings 8:14-15) his previous seizure of the Damascene throne, as did the Assyrians. As a precursor, the prophet Elijah had anointed both Hazael and Jehu to rule their respective kingdoms (1 Kings19:15-16).

A minority of scholars dispute this reading. Instead, they argue in favor of the occurrence two generations later at about 798 BC during battle against Bar-Hadad III (son of Hazael), based on references to “my father” whom he succeeded (2 Kings 13:24). That salutation seems inappropriate to Hazael, who gained power illegitimately. This scenario would identify Jehoahaz king of Israel as the fatal casualty (1 Kings 22:34-37), while his son Jehoash (v. 26 and also 2 Kings13:25) remained in Samaria. With his beleaguered army derided (2 Kings 13:7), the doomed ruler entered the fray, presumably joined by king Joash of Judah. According to this analysis, a redacting scribe anachronistically attributed this defeat to the despised Ahab.

These various interpretations promote different timelines separated by almost a half-century. But how has this come about? Supporting the consensus, the ending of one name reads “-ram” – rare in biblical literature, and so reasonably associated with Joram (or Jehoram), king of Israel, who succeeded his brother Ahaziah, son of Ahab in the mid-ninth century BC. Joram is to be distinguished from the king of Judah (or perhaps not), both of whom sported the same (or similar) name (see 2 Kings 3:1 and 8:16). Judah’s king named his succeeding son with the same name as his Israelite counterpart’s late brother. The minority view emphasizes the initial salutation, which attributes authorship to the successor of Hazael.

The surrounding geopolitical landscape fostered considerable turbulence. In the ninth century BC, Assyrian emperor Shalmaneser III struck out west towards the Mediterranean. At Qarqar in 853 BC, he confronted a powerful alliance that ended in apparent stalemate, as the Assyrians halted their advance. The Kurkh stele names the coalition leaders arrayed against the Assyrians, including “Ahab the Israelite” equipped with two-thousand chariots – the largest such contingent among those opposing factions. Sir Henry Rawlinson reprinted its text in the third volume of Cuneiform Inscriptions, as shown below with Ahab’s name outlined.

Shalmaneser III pressed again, invading Syrian territory successively in 849, 848, 845 and 841 BC. His final campaign culminates in Jehu’s coup marked by Israelite tribute presentation at Mount Carmel. The Assyrians commemorated this foreign submission on the Black Obelisk carved from limestone that was erected in 825 BC. The second level of panels depict “Ya-hu-a” (in outline) “mar-um-ri-i” (recognizing continuation of the Omride dynasty) while the Israelite king prostrated himself and brought silver as tribute. Tribute constituted an effective mechanism for vassals to recognize the dominant suzerainty of the conquering empire.

Unfortunately for Jehu, the Assyrians withdrew northward shortly afterwards, leaving Israel and Judah to Hazael’s tender mercies, although Shalmaneser did return briefly to besiege Damascus in 836 BC. Spurred by Jehu’s overtures to their former common enemy, Aram-Damascus made frequent incursions into Israel in the latter half of the ninth century BC, as attested in the Hebrew scriptures (1 Kings 20:1-12; 2 Kings 6:8, 24 and 10:32-33). Perhaps Jehu’s cozying to Assyria and abandoning the coalition angered Hazael so as to seek revenge after the Assyrian withdrawal, despite their mutually arranged overthrows of their respective monarchs.

Attacks extended into the early eighth century against Jehu’s successor, Jehoahaz (2 Kings 13:3, 22) as well as onward to Judah (2 Kings 12:18 and 2 Chronicles 24:23). After Hazel died, Israel reclaimed northern Galilee following Syria’s defeat (2 Kings 13:25). Then presumably, Jehoash of Israel smashed the Aramaic commemoration dedicated at Dan and used some pieces to rebuild the city walls.

Conceivably, decades later a collection of taxes and mustering of men exemplified in the Samaria Ostraca enabled Jehoash to prevail against Hazael’s son Bar-Hadad III on the battlefield. A contemporaneous inscription from Hamath (Genesis 10:18; 2 Samuel 8:9; 1 Chronicles 18:9-10; Isaiah 10:9 and Amos 6:2) – the Stele of Zakkur (KAI 202) – commemorates divine victory over a formidable coalition led by Aram’s king. After whichever reversal against either Joram by Hazael or Jehoahaz by Bar-Hadad, the subsequent victor dismantled the stele at Tel Dan and buried at least part of its arrogant tale, effectively “canceling” the public display of that earlier humiliation.

When one is lacking access to modern social media platforms/tools while confronting an offensive triggering message that is set in stone, all one merely needs is a mallet. In such cases, a temper tantrum offers fleeting visceral satisfaction, but history suffers permanent informational impoverishment for it. We therefore find that preservation of curated selections from the past requires both diligent focus and vigilant protection.

The temptation to obliterate what precedes our introduction lies deep in our psyches. Apart from the millions viciously killed in the Great Leap Forward, the example of the Cultural Revolution’s destructive wake that Mao Zedong unleashed in the mid-1960s epitomizes his vindictive savagery towards Chinese ancestral legacy. The mob’s perverse proclivity towards “cancellation” obliges our refusal to acquiesce. But we can be assured that non-woke folks who actually care about truth and the future will continue to resist the desecration of our historical heritage, while honoring its occasionally successful endeavors.